Overview#

Feel free to skip to the hacking part directly if you don’t care about the basics of BLE

Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE)#

Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), is a Protocol spoken by many modern devices. The key difference to regular Bluetooth is that BLE is intended to consume less power while maintaining a similar communication range. This is achieved by implementing a always off technology, meaning solely short amounts of data are transmitted if and only if it is required. BLE uses the IMA (2.4 GHz) band with 40 channels, where 3 of these are used for advertising.

Central and Peripherals#

Assume we just bought a super cool new Fitness tracker, which also provides an IOS or Android application for our phone. When using the tracker, for example, to measure our heart rate, it communicates directly to the app, which then displays the data. This is a typical example of BLE communication, where the data is sent from one device to another. We typicall call these devices peripheral (sending) and central (receiving). Peripherals (tracker) are mostly small, low-energy devices that can connect to more powerful central devices (phone).

Advertising#

Cool, but how do these devices even know about each other’s presence?

Great questions, I’m glad you asked! The magic word here is advertising.

Our tracker (peripheral) constantly sends out advertising data every X ms (defined by an advertising interval), which a central device can then look out for. If the central device is ready to listen to these packets, it will respond with a scan response request.

For our example, the application on our phone will scan for the specific MAC address of our tracker, which was probably programmed within the application itself, and sends a response request back to the tracker when found.

Regarding the advertising data, different things such as the device name, TX Powerlevel, ID, or services are included.

How BLE works#

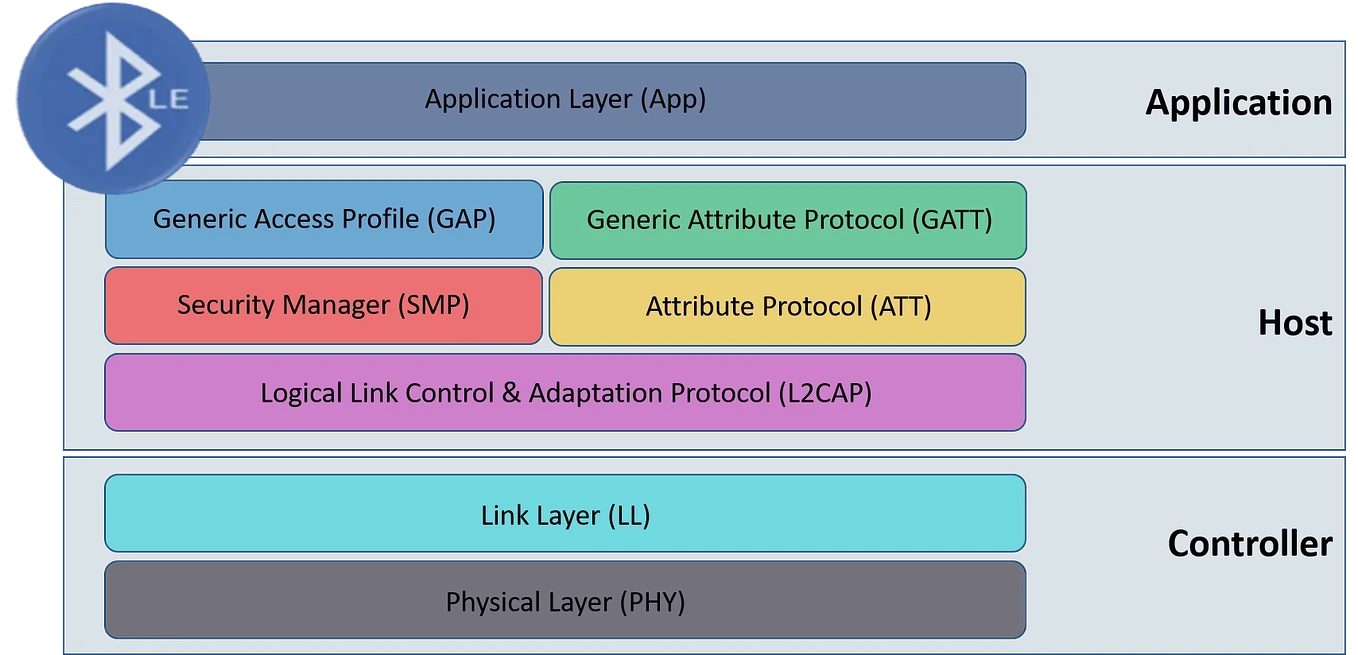

Let us now investigate how the BLE Protocol operates, by taking a look at the different layers it consists of. As a whole, the protocol can be broken down into the following layers and sub-protocols:

Generic Access Profile (GAP)#

GAP implements the advertising process we discussed before. It is also responsible for defining devices’ roles in BLE communication. As for the roles, the following once exists: Broadcaster, Observer, Peripheral, and Central. Depending on the connection type: Broadcast (one-to-many) or Unicast (one-to-one), devices will be assigned one of those. Peripheral and central for unicast, broadcaster, and observer for broadcast.

Generic Attribute Protocol (GATT)#

Now, one of the other very important sub-protocols is GATT. This protocol defines how two BLE devices exchange data with each other. This data exchange is initiated after the advertising process (GAP) has been completed. Now, the core concept of data exchange lies in so-called characteristics and services.

Characteristics#

In simple words, a characteristic can be thought of as a basic “API endpoint” (e.g. GET /tracker/heart_rate). It can be accessed and called by devices to either read, write, or listen and notify for any updated data. However, in terms of BLE we often encounter that those “API endpoints” are not directly translated into something useful such as GET /tracker/heart_rate, but a UUID like AAE28F0071B534ABCF182F...

Mostly, if we see such a UUID we can assume that this is a custom-created characteristic by the manufacturer. At the beginning of a connection, a series of characteristics and the service name are exchanged by the devices. This way the central device can identify the service.

The interesting part about BLE is that most devices are configured to accept connections by any device without pairing or bonding first. This allows us to interact with the device and retrieve the services and characteristics. Although, those can be configured to require pairing or bonding as well, but more on that later.

Services#

A service is simply a bundle of different characteristics. In the example of our “API endpoint”, it could be the /tracker/ path that bundles different functionality such as /heart_rate. Commonly, bundling characteristics is done in a logical way, such as we did with the tracker and the corresponding heart rate function.

Hacking BLE#

Prerequisites#

Hacking protocols like Bluetooth, WiFi, Zigbee, etc. mostly require external hardware to do so. For BLE my recommendation is to get an nRF52840 Dongle for the beginning. It costs around 10-20$ and features multiple protocols, already compiled programs such as a BLE sniffer, and other super useful stuff.

Enumeration#

Let us see if the interface we want to use even shows up on our PC by using hci tools. HCI stands for Host Controller Interface and is used between the controller and host layer of the BLE stack.

❯ hciconfig

hci1: Type: Primary Bus: USB

BD Address: 5C:F3:70:XX:XX:XX ACL MTU: 1021:8 SCO MTU: 64:1

UP RUNNING

RX bytes:1414 acl:0 sco:0 events:84 errors:0

TX bytes:4689 acl:0 sco:0 commands:69 errors:0

hci0: Type: Primary Bus: USB

BD Address: D8:80:83:XX:XX:XX ACL MTU: 1021:6 SCO MTU: 240:8

UP RUNNING

RX bytes:3551738 acl:1126 sco:636 events:436453 errors:2

TX bytes:363080346 acl:422502 sco:362 commands:2761 errors:0

Great, let’s do our first quick LE scan to see the devices around us:

❯ sudo hcitool lescan

LE Scan ...

38:18:4C:24:30:3E LE_WH-1000XM3

38:18:4C:XX:XX:XX (unknown)

...

Now for this, I will use my headphones (LE_WH-1000XM3) as an example. If you find the desired MAC address of the device you are interested in, we can proceed and enumerate the services and characteristics using bettercap.

❯ sudo bettercap --eval "ble.recon on"

bettercap v2.40.0 (built for linux amd64 with go1.23.5) [type 'help' for a list of commands]

[01:40:20] [sys.log] [inf] gateway monitor started ...

BLE » [01:40:21] [ble.device.new] new BLE device LE_WH-1000XM3 detected as 38:18:4C:24:30:3E (Sony Home Entertainment&Sound Products Inc) -71 dBm.

BLE » ble.show

┌─────────┬───────────────────┬───────────────┬────────────────────────────────────────────┬──────────────────────────────────────────────┬─────────┬──────────┐

│ RSSI ▴ │ MAC │ Name │ Vendor │ Flags │ Connect │ Seen │

├─────────┼───────────────────┼───────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────────────────────────┼─────────┼──────────┤

│ -74 dBm │ 38:18:4c:24:30:3e │ LE_WH-1000XM3 │ Sony Home Entertainment&Sound Products Inc │ │ ✔ │ 01:41:39 │

Checking the “Connect” field of the table, we can see that this device allows us to connect without any prior pairing or bonding.

BLE » ble.enum 38:18:4c:24:30:3e

[01:47:26] [sys.log] [inf] ble.recon connecting to 38:18:4c:24:30:3e ...

BLE »

┌──────────────┬──────────────────────────────────────┬─────────────────────┬─────────────────────────┐

│ Handles │ Service > Characteristics │ Properties │ Data │

├──────────────┼──────────────────────────────────────┼─────────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 0001 -> 0004 │ Generic Attribute (1801) │ │ │

│ 0003 │ Service Changed (2a05) │ INDICATE │ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ 0005 -> 0009 │ Generic Access (1800) │ │ │

│ 0007 │ Device Name (2a00) │ READ │ LE_WH-1000XM3 │

│ 0009 │ Appearance (2a01) │ READ │ Unknown │

│ │ │ │ │

│ 000a -> 0011 │ 69a7f243e52f4443a7f9cb4d053c74d6 │ │ │

│ 000c │ be8692b13b29410d94d350281940553e │ WRITE │ │

│ 000e │ 3f92019dac1d48dc9d9486a0fb507591 │ READ │ │

│ 0011 │ 5bc06a57f84d4086a65a2a238cb39cdb │ READ, WRITE │ insufficient encryption │

│ │ │ │ │

│ 0012 -> 001e │ fe59bfa87fe34a059d9499fadc69faff │ │ │

│ 0014 │ 104c022e48d64dd28737f8ac5489c5d4 │ WRITE │ │

│ 0016 │ 69745240ec294899a2a8cf78fd214303 │ NOTIFY │ │

│ 0019 │ 70efdf0043754a9e912d63522566d947 │ NOTIFY │ │

│ 001c │ eea2e8a089f04985a1e2d91dc4a52632 │ READ │ 02 │

│ 001e │ a79e2bd1d6e44d1e8b4f141d69011cbb │ WRITE │ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ 001f -> 002b │ 91c10d9caaef42bdb6d68a648c19213d │ │ │

│ 0021 │ 99d1064e451746aa8fb46be64dd1a1f1 │ READ, WRITE, NOTIFY │ insufficient encryption │

│ 0024 │ fbe87f6c3f1a44b6b5770bac731f6e85 │ WRITE, NOTIFY │ │

│ 0027 │ 420791c0bff54bd1b957371614031136 │ WRITE, NOTIFY │ │

│ 002a │ e4ef5a4630f94287a3e7643066acb768 │ WRITE, NOTIFY │ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ 002c -> 0031 │ fe03 │ │ │

│ 002e │ f04eb177300543a7ac61a390ddf83076 │ WRITE │ │

│ 0030 │ 2beea05b18794bb48a2f72641f82420b │ READ, NOTIFY │ insufficient encryption │

│ │ │ │ │

│ 0032 -> 0039 │ 5b833e056bc748028e9a723ceca4bd8f │ │ │

│ 0034 │ 5b833c116bc748028e9a723ceca4bd8f │ WRITE │ │

│ 0036 │ 5b833c136bc748028e9a723ceca4bd8f │ NOTIFY │ │

│ 0039 │ 5b833c146bc748028e9a723ceca4bd8f │ READ │ WH-1000XM3 │

│ │ │ │ │

│ 003a -> ffff │ 5b833e066bc748028e9a723ceca4bd8f │ │ │

│ 003c │ 5b833c106bc748028e9a723ceca4bd8f │ WRITE │ │

│ 003e │ 5b833c126bc748028e9a723ceca4bd8f │ NOTIFY │ │

│ │ │ │ │

└──────────────┴──────────────────────────────────────┴─────────────────────┴─────────────────────────┘

Awesome, now let’s check the table and what we see.

The first line looks like a “grouping” of the UUIDs below it. Remembering the sections before, those seem to be the services.

│ 0005 -> 0009 │ Generic Access (1800) │ │ │

│ 0007 │ Device Name (2a00) │ READ │ LE_WH-1000XM3 │

│ 0009 │ Appearance (2a01) │ READ │ Unknown │Below each of the services, we find the individual characteristics, and their properties (READ, WRITE, NOTIFY), as well as the data which bettercap automatically reads and displays for us. Further, we can see the memory location where the data is stored, referred to as handles.

│ 0005 -> 0009 │ Generic Access (1800) │ │ │

│ 0007 │ Device Name (2a00) │ READ │ LE_WH-1000XM3 │

│ 0009 │ Appearance (2a01) │ READ │ Unknown │Here it is always important to check out that the memory locations are overlapping, meaning there is no gap between memory addresses, e.g. [0001 -> 0004] -> [0005 -> 0009].. and so on. If there were gaps between the handles, this could mean that there are hidden services inside.

Further, some of those handles do require some sort of pairing or bonding, indicated by the insufficient encryption.

Now, if you take a look at the table again, you will see that there are a lot of custom-implemented services and characteristics displaying just a UUID. If we are planning to attack this device, we probably should know what the actual functionality behind each UUID is. For this, we will need to reverse engineer each of those characteristics by e.g. inspecting and experimenting with the traffic in Wireshark. However, this is a whole different topic and not in the scope of this blog article.

Reading and writing data#

So for reading data, we already saw that bettercap automatically reads and displays the data out of READ properties. However, we can also try to read data manually from a specific handle if we wish to do so.

❯ sudo gatttool -b 38:18:4c:24:30:3e --char-read -a 0x0039 | awk -F: '{print $2}' | xxd -r -p;printf '\n'

WH-1000XM3

For writing data to a handle we can do something very similar. However, since we haven’t reversed the characteristics, we have to guess which type of data is expected by the device. We can however use the --listen flag, which may return some information via the NOTIFY property within the service.

# We are trying to write a string, which is rejected

❯ sudo gatttool -b 38:18:4c:24:30:3e --char-write-req -a 0x0034 -n $(echo -n "test" | xxd -ps) --listen

Characteristic Write Request failed: Attribute value length is invalid

# We are trying to write a simple 0x00 byte, which is allowed

❯ sudo gatttool -b 38:18:4c:24:30:3e --char-write-req -a 0x0034 -n 00 --listen

Characteristic value was written successfully

Notification handle = 0x0036 value: 01

❯ sudo gatttool -b 38:18:4c:24:30:3e --char-write-req -a 0x0034 -n 01 --listen

Characteristic value was written successfully

Notification handle = 0x0036 value: 00

Notify#

More details on this topic can be found here

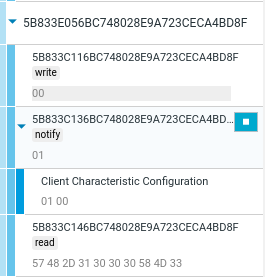

Sometimes, when using --listen, we won’t receive any data from a characteristic – even though it has the notify property. In these cases, we might need to configure the Client Characteristic Configuration Descriptor (CCCD) so that the server knows we want to receive notifications or indications.

The CCCD is a specific type of descriptor that allows a client to subscribe to updates for a characteristic that supports server-initiated operations (i.e., notifications or indications). In our fitness tracker example, the phone can use the CCCD to subscribe to the heart rate measurement characteristic and receive updates automatically, rather than having to poll for the data.

For our theoretical example, let’s choose the service with UUID 91c10d9c... that spans handles 0x001f to 0x002b. Assume that the CCCD for the characteristic is located at handle 0x002b (which has the required read and write permissions). We would then execute char-write-req 0x002b 0100 to enable the notifications.

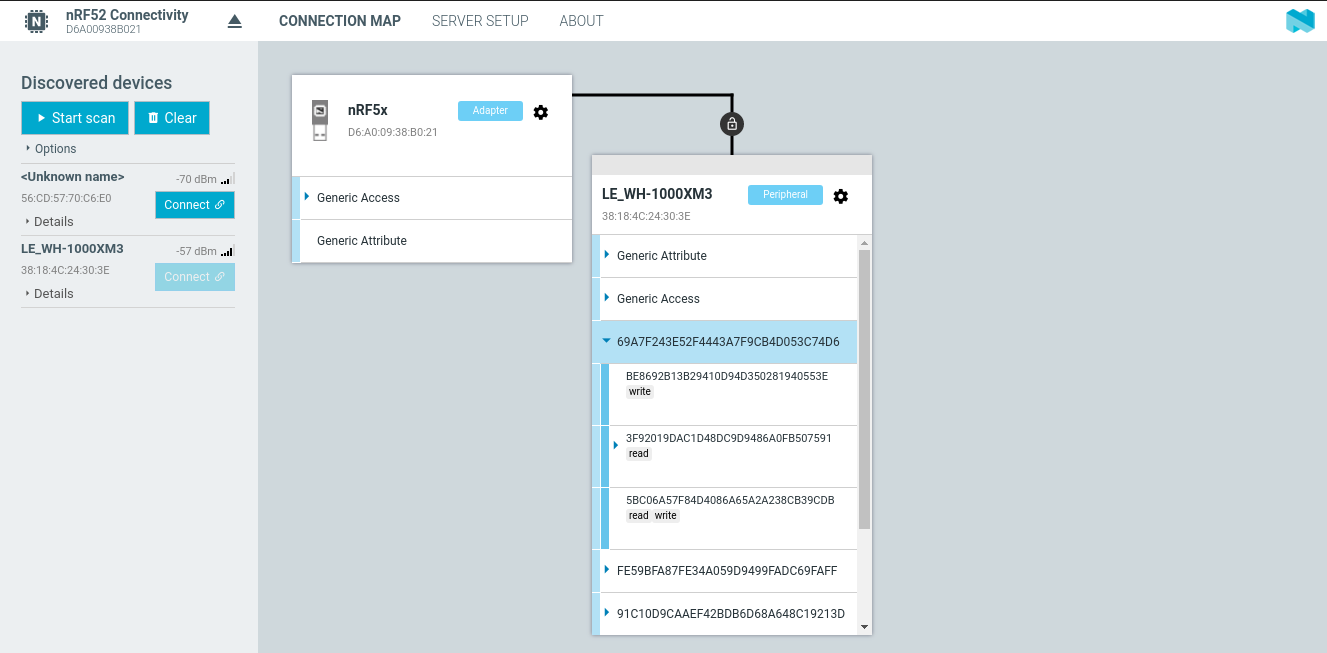

nRF Connect#

A way easier way compared to the manual one we saw before is to utilize the power of the nRF Dongle I recommended before. The application offers a lot of different programs, also BLE, that we can directly run with just a click.

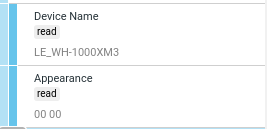

We get the same results by just clicking on “Start scan” and the corresponding “Connect” button. Further, we can also see that the software automatically reads out the data from READ properties if it is able to just like bettercap.

Writing and notifying is also just as easy as clicking a button or inputting the values. Although the sotware does not automatically decoded the bytes of 57 48 2D.. to WH-1000XM3, which bettercap actually did for us.

│ 0039 │ 5b833c146bc748028e9a723ceca4bd8f │ READ │ WH-1000XM3 │

Summary#

In this article, we delved into the essentials BLE and its inner workings. We began by exploring the fundamental differences between BLE and classic Bluetooth, emphasizing BLE’s low-power communication and its unique advertising mechanism. Key BLE components such as GAP and GATT were discussed, highlighting how they define device roles, advertising, and data exchange through services and characteristics.

We then transitioned into the practical side of BLE hacking. Using tools like bettercap and gatttool, we demonstrated how to enumerate nearby BLE devices, inspect their available services, and interact with their characteristics – whether it’s reading, writing, or enabling notifications. The article also covered common challenges such as handling hidden services as well as a brief overview of how modern tools like the nRF Connect suite can simplify these tasks.

Overall, this guide provides a solid foundation for understanding BLE technology and its vulnerabilities, paving the way for further exploration and security testing in the ever-evolving landscape of IoT and wireless communications.